|

| Gazebo at the Los Angeles County Arboretum and Botanic Garden. Photo credit: Tracy Hall. |

Given that “arbor” means “tree” in latin, “arboretum” implies a focus on trees, woody species. Indeed, someone wrote on Wikipedia that in the narrowest sense, an arboretum is exclusively a collection of trees. If the definition of “tree” includes all woody plants, then an arboretum may also include shrubs and vines.

In contrast, a botanical garden typically exhibits a “wide range of plants” (Wikipedia; American Public Gardens Association). Sometimes that includes a significant number of trees in my experience, and that’s where a botanical garden can start to resemble an arboretum. In nature, woody species coexist with herbaceous plants after all. Conversely, an arboretum can start to look like a botanical garden when in addition to trees, it contains noteworthy collections of herbaceous plants. Then you have places like the Los Angeles County Arboretum and Botanic Garden that proclaim outright to be both.

Hill (1915) traces the history of most modern botanical gardens to “physic gardens,” European gardens focused on medicine and research, specifically the “hortus” (vegetable garden with eighteen beds probably arranged in two rows of nine) and “herbularius” (physic garden with sixteen beds of plants, placed near the infirmary, probably for convenience) of monasteries like that of St. Gall in the ninth century. (An interesting side note, he recalls Gregor Mendel’s famous genetic experiments on peas, which Mendel completed as a monk “in the monastic garden at Brunn.”)

|

| Landscape plan of the physic garden at the Monastery of St. Gall, excerpted from Hill (1915) names the plants to be planted in each of the numbered planting beds. |

Universities and monasteries and private landowners established physic gardens to ensure a clear source of medicinal plants supplied apothecaries (“to safeguard the Practitioner against the Herbalist” and drug peddlers), and in Europe these gardens have become botanical gardens. In the mid-1500s, non-medicinal plants, especially rare plants, were introduced to physic gardens “for the purpose of observing and admiring nature.” By the latter half of the sixteenth century, “the tendency was to grow as many plants as possible, and a healthy rivalry commenced...as to who could show the greatest number of different species in cultivation.” (Hill 1915)

|

| Hill said the historic Botanical Garden of Padua (Orto Botanico di Padova) in Italy privately established in 1545 was preserved much in its original sixteenth century condition (at the time of writing in 1915) and is a good example of garden design popular in Europe in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. The garden is a UNESCO World Heritage Site. Photo credit: Xiquinho Silva. |

The practice of collecting medicinal and economically important plants in gardens predates physic gardens. Hill writes, “The Chinese...should, as might be supposed, be credited with being the real founders of the idea of botanic gardens, since it is clear that collectors were despatched to distant parts and the plants brought back were cultivated for their economic or medicinal value.” He notes Emperor Shen Nung from the twenty-eighth century B.C. who supposedly “tested the medical qualities of herbs and discovered medicines to cure diseases.”

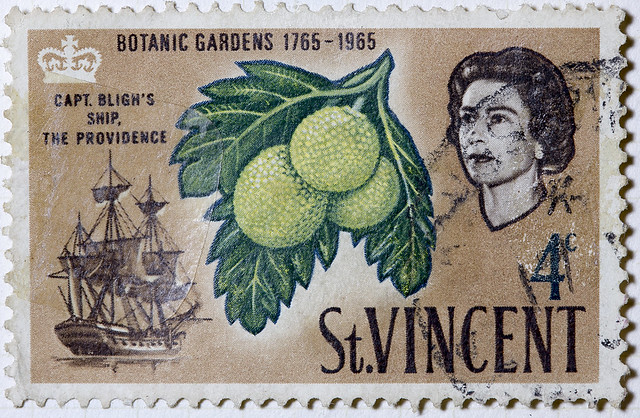

Whereas the driving force behind the founding of botanical gardens in temperate climates was to produce herbs for medicinal use and research, gardens were created in the tropics (beginning in 1764 on the Island of St. Vincent by the British) to collect economically important plants (spices in particular).

|

| Botanic Gardens St. Vincent was the first garden created by the British in the tropics for the purpose of collecting economically important plants. Plants destined for the St. Vincent garden were lost in the 1790 mutiny of the Bounty. In 1793, breadfruit and other plants from the Pacific were introduced to the garden by Captain Bligh. Photo credit: Mark Morgan. |

Today, the American Public Gardens Association defines “botanical garden” (or botanic garden, the terms are used interchangeably, although “botanic” is said to be “generally reserved for the earlier, more traditional gardens” (Wikipedia) or just an older term) by outlining five requisite features. The garden must be open to the public; focus on aesthetics, education, and/or site research; maintain plant records; employ at least one professional; and facilitate plant identification through labels or other means.

The word “arboretum” was invented in 1833 by the English, although the practice of collecting tree specimens from around the world and planting them in a garden setting apparently dates back to the Egyptians. A brief University of Texas article traces the arc of arboreta history from private collections of trees by Egyptian pharoahs in ancient times to the development of public “tree gardens” in Europe in somewhat less ancient times, to the spread of arboreta to other cities in the late 1800s with the addition of scientific research to their mission, to the expansion in mission in modern times to include conservation.

ArbNet provides accreditation for arboreta worldwide in four “levels,” the minimum criteria being a publicly accessible site with 25 woody plant species, at least one employee or volunteer, a governing body, and an arboretum plan, while Level IV accreditation requires scientists publishing research and the management of tree collections for conservation purposes. No such accreditation process exists for botanical gardens; any garden can be called a botanical garden.

To make a long story short, botanical gardens derive from medicinal herb gardens and spice gardens (one has to wonder whether some of the latter were not collections of trees) while arboreta seem to derive from a human fascination with trees and their diversity. ArbNet accredited arboreta must contain many different woody species while botanical gardens may contain woody species but don’t have to. An arboretum can be a botanical garden, and a botanical garden can be an arboretum.

There are a few electronic maps that show the locations of gardens and arboreta around the world:

MapMuse (U.S. focused)

ArbNet accredited arboreta

Morton Register of Arboreta (lists woody plant focused arboreta and gardens worldwide, including those not ArbNet accredited, and highlighting those that are)

American Public Gardens Association Garden Map (botanical gardens)

-

The History and Functions of Botanic Gardens by Arthur W. Hill (Annals of the Missouri Botanical Garden, 1915)

http://www.jstor.org/stable/2990033

University of Texas at Austin PDF on arboreta history

http://www.esi.utexas.edu/files/079-Learning-Module-Arboretums.pdf

Wikipedia article “Arboretum”

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Arboretum

Wikipedia article “Botanical Garden”

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Botanical_garden

A more detailed description of herbularius and hortus is found in The History of Gardens by Christopher Thacker, accessible via Google Books at:

https://books.google.com/books?id=1gn8hIgwg-gC&lpg=PA81&ots=_FRg00dJKV&dq=st%20gall%20hortus%20herbularius&pg=PA81#v=onepage&q=st%20gall%20hortus%20herbularius&f=false

Botanic vs Botanical on Grammarist

http://grammarist.com/usage/botanic-botanical/

Gregor Mendel

http://www.nature.com/scitable/topicpage/gregor-mendel-a-private-scientist-6618227

UNESCO page for the Botanical Garden of Padua / Orto Botanico di Padova

http://whc.unesco.org/en/list/824/

No comments:

Post a Comment