|

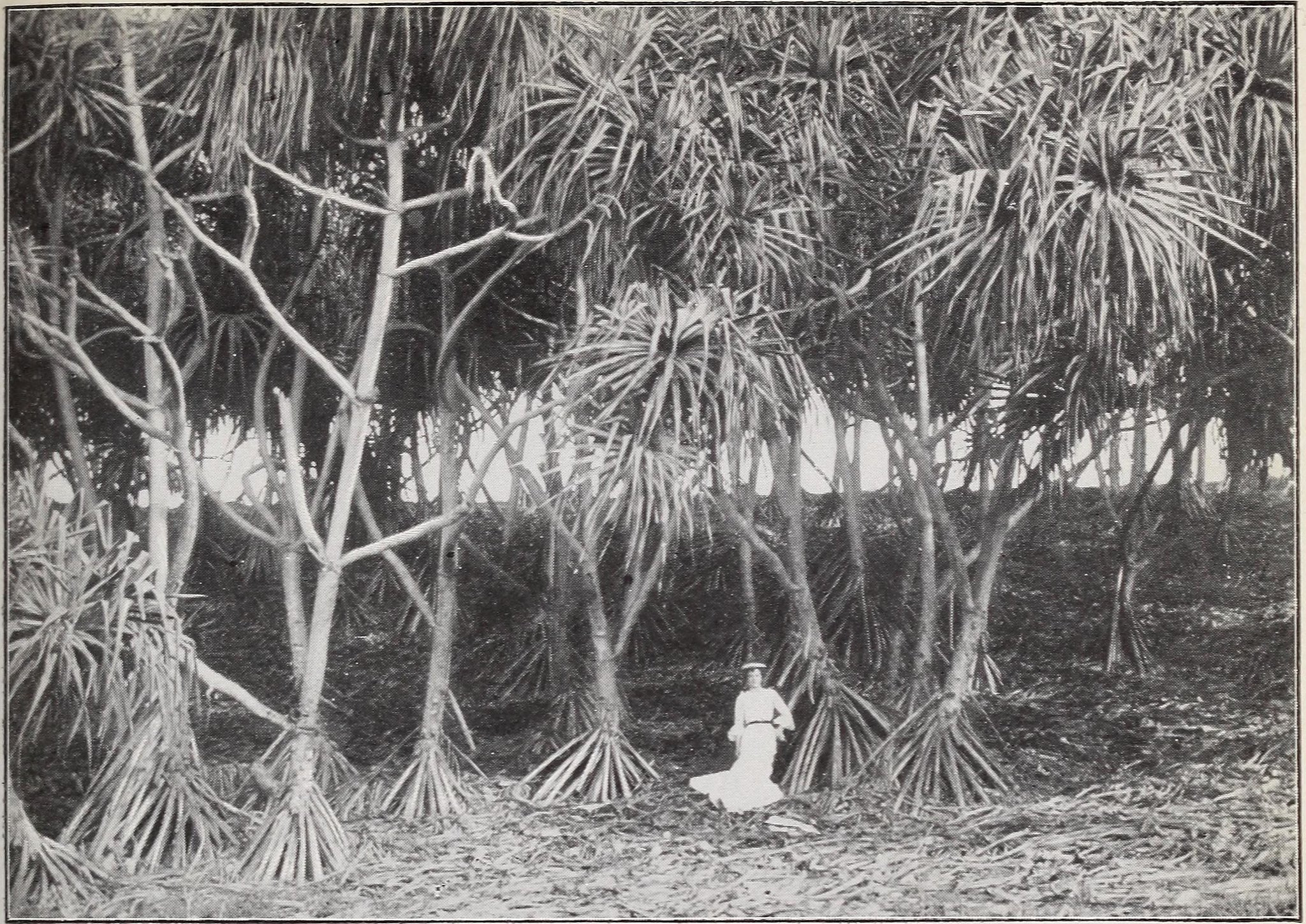

| Hala grove in Hawaii ca. 1901. Image credit: Internet Archive Book Image. |

Native to Hawaii, the pū hala (hala; Pandanus tree; screwpine; Pandanus tectorius S. Parkinson ex Z) was as useful as the coconut in ancient times, but is getting harder to find.

Prior to the turn of the last century, many dense groves of hala (screwpine; Pandanus tectorius S. Parkinson ex Z) abounded in Hawaii. One account described hala as the primary species seen when descending from the pali to Mōkapu in windward Oahu in 1831.

|

| Looking toward Mōkapu from Nuuanu Pali in 2010: no hala in sight, at least from this perspective. Photo credit: Ken Lund. |

|

| Wider landscape view from Nuuanu Pali in 2014. Photo credit: Prayitno. |

Hala is an indigenous (native), dioecious coastal tree in Hawaii, capable of withstanding wind and salt. Its range can extend to valley slopes up to or beyond 600 m (1969 ft) elevation.

Groves of hala typically existed near settlements in ancient Hawaii. Although it is not known whether they were planted intentionally or people simply chose to settle near existing groves, evidence exists to show hala was at least occasionally planted near homes, probably when there were no groves nearby or an outstanding tree was encountered. Hala does not appear to have been cultivated in Hawaii (i.e., intentionally selected to develop cultivars), however, and while several species and cultivars exist across the Pacific, only one species of Pandanus is considered native to Hawaii.

In a method called pāhala, taro was sometimes planted in holes made in the lava around the trees in Puna groves that had been filled with mulched lau hala (lit. Pandanus leaf). Burned hala branches reduced to ash were used as a soil amendment.

Lau hala was woven into hats, mats (eighteen different types, chiefs stacking as many as sixty to make a bed), canoe sails (by sewing mats together), baskets, pillows, kites, and fans, and used for making medicine, exterior thatching (not as good as pili grass, but better than the other alternatives), interior wall finishes, rope, fishing traps, adding color to surfboards (the leaves were first burnt), to wrap "hard" poi (pounded taro made without water), and water catchment. Compared to coconut thatching that lasted just three years in coastal areas with low rainfall, lau hala roofing reportedly had a lifespan of fifteen years. The fruit and root of the tree were used to treat various ailments; the keys strung into lei or used as a brush; the flowers used as a perfume and aphrodisiac; the wood used in woodworking; and the seeds provided famine food.

|

| Hawaii homes thatched with lau hala, ca. 1880s. Photo credit: Hawaii State Archives. |

|

| Preparing hala fruit for lei-making, ca. 1930s. Photo credit: Hawaii State Archives. |

|

| Lei made from the hala fruit in modern times. Photo credit: Wendy Cutler. |

|

| 1906 advertisement in The Pacific Commercial Advertiser for a hala hamper. Image credit: Evening bulletin. (Honolulu [Oahu, Hawaii), 07 Dec. 1906. Chronicling America: Historic American Newspapers. Lib. of Congress. <http://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn82016413/1906-12-07/ed-1/seq-3/> |

|

| Modern placemat woven from lau hala. |

The weaving of hats is arguably the most popular use of lau hala in Hawaii today, and it appears this trend dates back at least a century. In order to weave a hat, or anything else, from the hala leaf, one must make the leaves workable through a labor-intensive processing ritual.

David Malo (1793-1853) wrote in Hawaiian Antiquities (1903) that preparation of lau hala began with women beating the leaves with sticks. The leaves were wilted over a fire, dried in the sun, separated according to age, rolled into bundles called kūka'a, and later unrolled and broken down into narrower strips for weaving.

|

| Piles of lau hala. Photo credit: Hawaii State Archives. |

|

| Making kūka'a (rolls of lau hala). Photo credit: Hawaii State Archives (RKO Pathe Inc.). |

|

| Making kūka'a in 1935. Photo credit: Hawaii State Archives (Pan Pacific Press Bureau). |

|

| Making the leaves into narrow strips for weaving in 1935. Photo credit: Hawaii State Archives. |

|

| Weaver Pila'a Kilani in Pukoo, Molokai working on a lau hala mat in 1913. Photo credit: Hawaii State Archives (Ray Jerome Baker). |

The process of preparing lau hala for weaving has broadly remained the same over the years, although modern tools and dyes (like Rit dye) have been introduced. This video is a great explanation of how lau hala is prepared for weaving today using modern tools.

Many different styles of hats have been made over the years. Paniolo wore lau hala hats in the mid 1800s, plantation workers donned them in the early 1900s, and military personnel took an interest in lau hala products, increasing demand through the 1940s. A 1945 newspaper article reported that most of the lau hala came from the Puna and Hamakua districts on the Big Island, with eighty-five percent of production traced back to Kona (see Meilleur et al. (1997)).

In the early 1900s, hat weaving was taught in schools, and garnished awards. A lau hala hat could be sold for $2 or $3 in 1901 ($57 to $86 in 2015 dollars). For comparison, (perhaps fancier) hats made of peacock feathers, popular in the King Kalākaua era when such feathers were more abundant, went for $25 ($718 in 2015 dollars).

|

| Pre-1900 portrait of Moloka'i woman wearing lau hala hat. Photo credit: Hawaii State Archives. |

|

| Woman weaving hat in 1935. Photo credit: Hawaii State Archives. |

|

| Dorothy Enzor models a hat (by Elsie Krassas?) decorated with dried limu (seaweed) in 1935. Photo credit: Hawaii State Archives. |

|

| Different hat styles ca. 1935 made of lau hala and kapa. Photo credit: Hawaii State Archives. |

William Brigham noted a decline in the art of lau hala weaving in the latter half of the 1800s through this personal observation:

"Puna was a famous region for hala mats, and in 1864...when journeying through that district with that noble missionary the Reverend Titus Coan...[I] saw many a party in the curious open caves (caused by a breakdown of the lava crust in some of the many streams of lava, ancient and recent, that form much of the surface of Puna) busily engaged in weaving mats...

...A quarter of a century later [Editor's note: that would be 1889] in traveling the same road with a younger companion the scene was greatly changed: the caves were there, the hala trees were there, but the inhabitants had gone, and for sixty miles there was nothing but a few deserted churches and some aged breadfruit trees to tell that once people had lived there...

...Fifteen years later [Editor's note: 1904] the scene had again changed owing to the opening of roads and the cultivation of sugarcane, but the present inhabitants were not the old natives, and the mat making is only here and there continued when there is a chance to sell to the foreigner...

...This was especially the work of old women, and as late as 1888 I saw an ancient dame near Kailua, on the western side of Hawaii, continuing the work of her ancestors. She was reputed to have outlived the century mark, cramped in every joint, unable to stand erect, kenneled in a grass hut not four feet high, she was still busily and cheerfully trimming hala leaves with a sharp shell. As I watched her...there came back to my memory most vividly the groups of old women I had seen in Puna doing the same thing..."

Weaving was revived in the 1930s, which may explain the number of photos related to lau hala in existence from that era at the Hawaii State Archives, but is again declining. Milliners of lau hala still exist today, but their products are often highly prized gifts for dear friends with few available commercially.

In 2010, Big Island Television featured Aunty Elizabeth Lee, contemporary master weaver, who described how to prepare lau hala and why she founded the weaving conference Ka Ulu Lau Hala 'O Kona in this video.

Another contemporary weaver, librarian Lynette Roster, spoke about weaving and designing hats and how weaving can be a spiritual experience in a video produced by Punahou School alumnus Alayna Kobayashi in 2014.

Weaving communities have expressed concern over the years about the future of the art. The art surely seems less prevalent than in earlier times, perhaps because it is labor-intensive; modern materials, manufacturing methods, and shipping provide inexpensive, readily available substitutes for Hawaii's lau hala products; and hala trees are getting harder to find.

Sugar cane production and development have encroached on hala habitat, making groves like the one below scarce. Several anecdotes claim the presence of hala is declining in Hawaii - certainly coastal and agricultural-zoned land has increasingly been developed - but no one appears to have documented this in a scientific way.

|

| Hala grove in Puna, Hawaii in 1888. Image credit: Internet Archive Book Image. |

One place that Pandanus can be found today is in landscaping, although the species or cultivars chosen for this purpose sometimes appear to vary, especially in recent years (author's personal opinion).

|

| Pandanus at Iao Tropical Gardens on Maui. Photo credit: Forest and Kim Starr. |

|

| Pandanus in landscaping at Schofield Barracks on Oahu ca. 2007. Photo credit: Cliff. |

|

| Pandanus (left) at the Aulani resort in Ko'olina on Oahu next to a large, conspicuous cactus and various palms. Photo credit: Joel. |

One study found hala forest replaced Metrosideros polymorpha ('Ōhia lehua) treeland (open canopy stands) in succession on bare Big Island lava flows within the plant's coastal range.

'Ōhia lehua seems to rarely be used in landscaping, at least where it isn't already growing, perhaps because it is slow growing or maybe it does better at higher elevations, but its form is surely a beauty to look at. It would be interesting to see hala and 'Ōhia lehua paired in a landscape design, especially given the successional pattern noted above.

For comparison, below are some images of Pandanus tectorius in the wild.

|

| Pandanus cliffside in Waipio, Maui. Photo credit: Forest and Kim Starr. |

|

| Pandanus tectorius amongst naupaka at Kipahulu, Maui. Photo credit: Forest and Kim Starr. |

|

| Pandanus tectorius grove, aerial view, Waipio, Maui. Click link to view larger --> Photo credit: Forest and Kim Starr. |

|

| Pandanus tectorius at Keanae, Maui. I think there is at least one 'Ōhia lehua tree (rightmost tree) in this shot. Click link to view larger --> Photo credit: Forest and Kim Starr. |

|

| Pandanus tectorius at Oheo, Maui. Photo credit: Forest and Kim Starr. |

Sources and/or further reading:

Meilleur, Brien A., MaryAnne Maigret, and Richard Manshardt. Hala and Wauke in Hawaiʻi. Vol. 7. Bishop Museum Pr, 1997.

Malo, David. Hawaiian Antiquities:(Moolelo Hawaii). Vol. 2. Hawaiian Gazette Co., Ltd., 1903. Electronic copy

Little, Elbert L., and Roger G. Skolmen. Common forest trees of Hawaii. US Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, 1989. PDF copy

"The Making of Native Hats"

Atkinson, I. A. E. "Succesional trends in the coastal and lowland forest of Mauna Loa and Kilauea volcanoes, Hawaii." Pacific Science 24.3 (1970): 387-400. PDF copy

"The Making of Native Hats"

The Pacific commercial advertiser. (Honolulu, Hawaiian Islands), 12 Jan. 1901. Chronicling America: Historic American Newspapers. Lib. of Congress. <http://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn85047084/1901-01-12/ed-1/seq-15/>

"Art of Weaving Among Hawaiians"

The Pacific commercial advertiser. (Honolulu, Hawaiian Islands), 17 July 1906. Chronicling America: Historic American Newspapers. Lib. of Congress. <http://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn85047084/1906-07-17/ed-1/seq-5/>

Memoirs of the Bernice Pauahi Bishop Museum of Polynesian Ethnology and Natural History, Volume II (Bishop Museum Press; 1906-1909)

http://www.agroforestry.net/images/pdfs/P.tectorius-pandanus.pdf (PDF)

http://www.agroforestry.net/images/pdfs/Metrosideros-ohia.pdf (PDF)

http://www.ntbg.org/plants/plant_details.php?plantid=8353

No comments:

Post a Comment