|

| Duku (langsat; Lansium domesticum) agroforest in Indonesia, according to the photographer, although it does not appear to be multi-story. Photo credit: Wibowo Djatmiko. |

If you were tasked with planting several trees, how would you arrange them? The natural tendency is probably to space them evenly and plant them in parallel rows after clearing the area of weeds and other plants. This is what we are often taught as children.

|

| New England apple orchard. Photo credit: Liz West. |

In farming, evenly spaced parallel rows are probably the most practical arrangement from the perspective of mechanized agriculture. The rows are wide enough to accommodate necessary equipment for maintaining the fields, and there is ample space between trees to conduct routine maintenance and prevent competition, thereby maximizing yields.

|

| Sunrise in a Thai rubber plantation. Photo credit: Theerawat Sangprakarn. |

Planting evenly spaced trees in parallel rows on a sizeable scale forms a plantation. Plantations often have uniform stands such that all trees in the stand are planted at the same time and are the same age. This results in a distinctive uniformity easy to spot, even at a distance.

|

| Eucalyptus grandis plantation in Hamakua, Hawaii. Photo credit: Forest and Kim Starr. |

For contrast, an image of Big Island 'Ōhi'a lehua forest near Kilauea, Hawaii is below. Hamakua is on the same island, further north and east. Note the irregular spacing, non-uniform tree diameters, and greater species diversity in the Kilauea forest compared to the eucalyptus plantation. The point of this comparison is merely to illustrate general visual differences between plantation and a more complex forest system. Hamakua has been agricultural land for probably centuries, and it is possible the pre-agriculture cover type was not 'Ōhi'a lehua forest.

|

| 'Ōhi'a lehua is a typical canopy species in forests on the Big Island in the Volcano area. Photo credit: Tim Wilson. |

In forestry, sometimes uneven aged stands are produced where the stand consists of trees of different ages. Instead of harvesting the entire stand at once, only certain trees within the stand are harvested. This creates discrete openings in the forest canopy to allow a new sapling to take its place. Clear-cutting an even aged stand quickly transforms closed-canopy forest to a patch of open field, whereas the forest canopy can remain mostly intact in uneven aged stands except for those small, localized openings.

|

| Industrial forest management on the Olympic peninsula in Washington state. Clear-cutting also creates many edges around the perimeter of the patch. Photo credit: Sam Beebe. |

|

| Patches of forest in Garibaldi Forest in central Oregon are selectively thinned to mimic natural disturbance. Photo credit: Sam Beebe. |

What is forestry? Wikipedia defines forestry as "the science and craft of creating, managing, using, conserving, and repairing forests and associated resources to meet desired goals, needs, and values for human and environment[al] benefits". Environmental benefits are of a physical nature, like improving drainage or nutrient cycling, as opposed to ecological benefits, which are of a biological nature (providing higher quality habitat for an endangered species, for example). The definition of forestry in theory is quite broad, but in practice, forestry, at least in the U.S., seems focused primarily on timber production. Many other useful products can be derived from trees, and these would typically fall within the field of agriculture.

-

The U.S. National Park Service describes

-

Agriculture, broadly and simply defined, is the science and art of farming. Although it seems sensible to include the farming of all things under the umbrella of "agriculture", forestry is typically considered a separate and distinct field. The study and practice of "agriculture", at least in the U.S., tends to refer to the farming of major industrial crops like corn, soybeans, and wheat at a large scale.

Agroforestry, a portmanteau of "agriculture" and "forestry", essentially means farming non-woody crops and trees in combination spatially and/or temporally. There are many different ways to use trees in an agricultural context, and most of those discussed in literature focus on either adding trees to a non-woody agricultural operation or incorporating non-woody plants into a plantation to provide some sort of environmental and/or economic benefit.

-

Wikipedia explains

-

Windbreaks are among the simplest use of trees in an agricultural system. Some crops do well in full sun conditions but need protection from wind. Strategic placement of rows of trees can provide a buffer without shading crops.

|

| Trees as windbreaks. Photo credit: USDA National Agroforestry Center. |

Trees may be planted along waterways to stabilize banks, retain soil, and reduce erosion, effectively creating a buffer between the riparian system and farmland, or planted in strategically placed corridors (not necessarily in a straight line) to provide improved habitat connectivity.

|

| A riparian buffer zone established with trees. Photo credit: USDA National Agroforestry Center. |

In alley cropping, trees typically have a plantation-style arrangement, but fast-maturing crops may be planted in the understory space between the rows of trees to diversify or supplement a farmer's income while the trees mature.

|

| Corn provides a quicker return than walnuts that take longer to mature. Photo credit: USDA National Agroforestry Center. |

Some crops, like tea, actually do better under partial shade. Trees can be planted to provide shade, thereby improving the tea operation, while also providing a long-term crop or other environmental benefits.

|

| Tea plantation with shade trees in India. Photo credit: Ajay Tallam. |

These are slightly more complex systems - as the farmer, you now have to manage two different crops instead of just one - but in addition to potential economic benefits, there may also be environmental benefits.

Nitrogen-fixing cover crops can be sewn amongst trees to improve soil fertility, reduce erosion, and increase soil water retention. Similarly, nitrogen-fixing trees can be planted amongst crops that require a lot of nitrogen to improve yields and soil fertility. Such crops could also be planted near existing leguminous trees.

| Trees like Faidherbia albida (background) can fix nitrogen, from the air into the soil, that crops like the sorghum in the foreground can then access. Photo credit: Marco Schmidt. |

Continuing along the gradient of agroforestry complexity is silvopasture, i.e., combining trees and livestock. Trees provide animals with needed shade and protection. Livestock breeds can be selected for milk, meat, or wool to provide income in the short term while trees mature. There may be other benefits related to nutrient cycling, soil fertility, or forage quality or abundance.

|

| The canopy of a slash pine plantation was opened up to convert the plantation to silvoculture, where goats graze in the understory. Photo credit: USDA National Agroforestry Center. |

Whereas silvopasture combines trees and livestock, forest farming combines trees and high value specialty crops like mushrooms, medicinal products, and floral or decorative products where production benefits from the forest environment.

|

| Shiitake mushroom production in a forest farm. Photo credit: Catherine Bukowski. |

Agroforestry in practice differs considerably in developed and developing countries. In the U.S., agroforestry seems to largely mean supplementing an industrial agricultural system with trees to derive environmental benefits, although other examples like forest farming do exist. Associated economic benefits like carbon offsets may also be achieved. In developing countries, economic benefits probably mostly stem from diversifying income and the associated increase in resilience that provides. Social benefits derived from agroforestry systems may be significant. The non-woody crops grown are often for subsistence. Agroforestry systems in developing countries can be highly species diverse.

The Burmese taungya system consists of long-term tree crops supplemented by short-term food crop mixes that change temporally. As trees mature, increasingly shade-tolerant short-term crops are selected as companions. When the canopy closes, tenant farmers tending the subsistence food crops must relocate and the agroforestry system reverts to plantation until the trees are harvested.

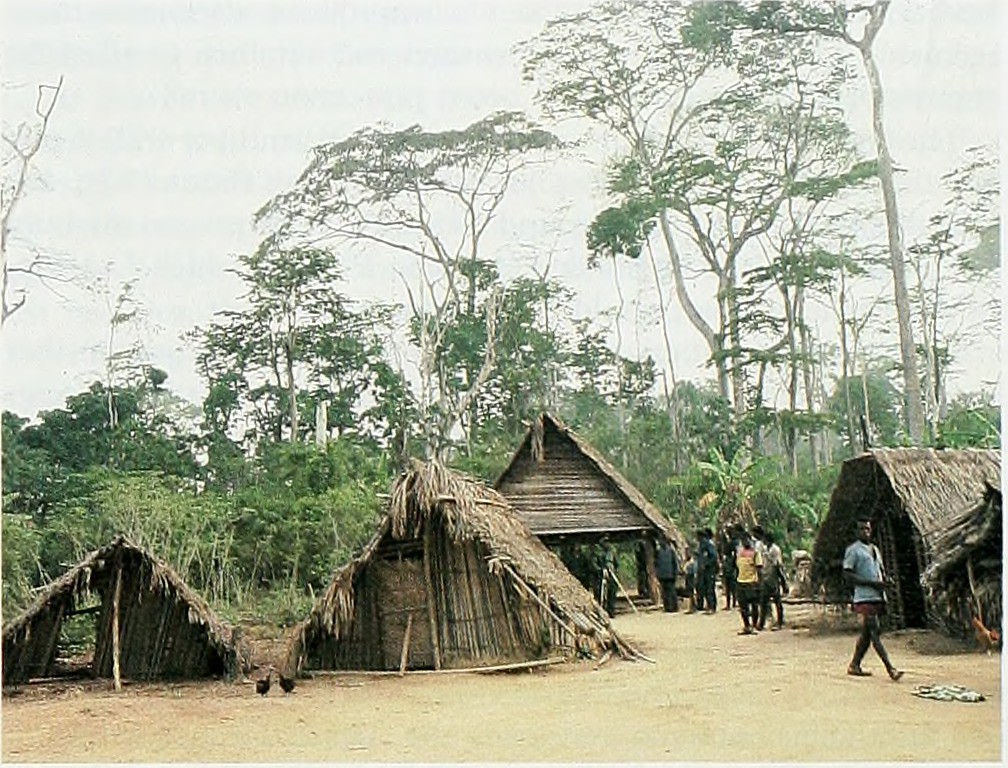

|

| Caretakers of this taungya in Guinea were supposed to move after three years, but did not. Photo credit: Internet Archive Book Image via The Conservation Atlas of Tropical Forests: Africa (1992). |

The most complex agroforestry system is the agroforest, a highly diverse, multi-story, closed-canopy system uncommon in the U.S., but found throughout the tropics in places like Indonesia, the Atlantic Forest in Brazil, the South Pacific, India, and Southeast Asia. Crops like rattan, cacao, coffee, durian, damar, and others are farmed in a setting that to the untrained eye can resemble "natural" forest. Existing forest may be cleared or thinned to make room for crops, or crops may simply be planted within an existing forest. Often centered around one or two commercial crops, the species list of an agroforest is typically extensive (possibly including more than seventy different species).

|

| "Multi-story" means that plants in the system occupy different vertical ranges. This garden has a groundcover understory, tree fern subcanopy, and trees forming the canopy. This is not an agroforest. Photo credit: /kallu. |

This method of farming is increasingly being replaced with full-sun monocropping systems, and gets relatively little attention in discussions about agroforestry. The inherent complexity seems to make agroforests higher quality habitat for forest wildlife than other agricultural systems. Agroforests are not a replacement for preservation efforts - they are not as "good" as "natural" (primary) forests - but have been found in some cases to serve as habitat or food source to endangered generalist species and are possibly the best potential land use in the buffer zone around preserves due to their closed-canopy structure that offers a better transition and reduced edge effects between open farmland or other intensive land uses and primary forest.

Photo and description of Yapese betel nut agroforest

Photo and description of Pohnpei betel nut and coconut agroforest

Photo and description of a coastal Yapese agroforest

De Foresta and Michon (1997) proposed a series of crop groupings to mimic succession on unwanted Imperata grasslands in Southeast Asia and permanently replace Imperata with a wholly man-made agroforest system that provides diversified income while minimizing the cost of establishing it.

De Clerck and Negreros-Castillo (2000) similarly proposed a wholly man-made agroforest system to replace slash-and-burn agriculture in a Mexican landscape, looking to the architecture of area homegardens to identify crops suitable for each niche in the spaciotemporal agroforest design. Coffee agroforests elsewhere in Mexico are sometimes established on former agricultural land through a series of actions that Bandeira, et al. (2002) concluded appears to mimic natural succession. It is not clear why De Clerck and Negreros-Castillo (2000) did not propose coffee agroforests: maybe the site conditions differed?

De Clerck and Negreros-Castillo (2000) credit Hart (1980) with demonstrating the potential for basing the structural design of a crop system on the architecture of an ecosystem "endemic" to the area by replacing individual species in the latter system with functionally analogous species (analogs), thus effectively mimicking the structure, and thereby function, of the naturally occurring system. There are efforts now to design "novel ecosystems" for conservation purposes, the theory being that establishing a stable system, even if it incorporates non-invasive introduced species and thus is not restoration to some pristine ideal, may provide resilience against invasions. In a way, aren't most ecosystems technically novel these days?

Regardless of the motivation behind the design of ecosystems - economics, conservation, restoration, aesthetics - our choices transform landscapes and how they interact, sometimes (as in the case of deforestation) irreversibly.

|

| Bolivian forest (top left corner), cleared (bottom), and converted to agriculture (right). Photo credit: Sam Beebe. |

No comments:

Post a Comment