|

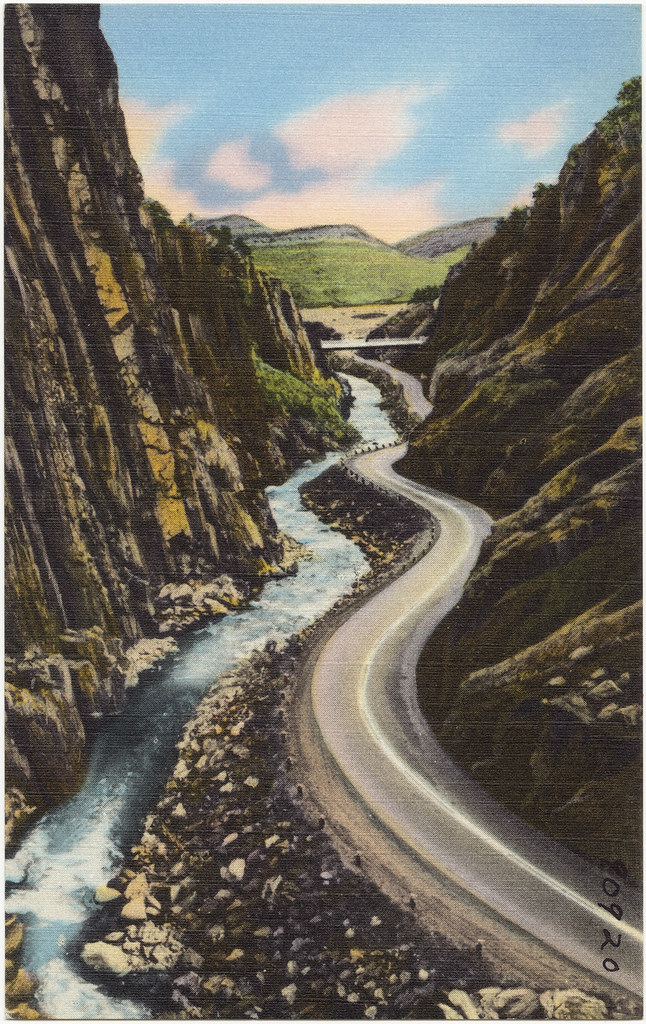

| Big Thompson Canyon, Highway US 34 to Estes Park and Rocky Mountain National Park in Colorado (ca. 1930-1945). Image credit: Boston Public Library. |

There's roughly seven weeks of summer officially left in 2016, which is enough time (according to at least one family) to embark on an epic adventure following a historic route dating back to the 1920s that links about half of the national parks that were in existence at that time.

Nowadays, there are so many roads it's overwhelming to even think about trying to nail down a specific route to go any distance in the US, and the need for more or better automobile connectivity is not what typically comes to mind when discussing roads and connectivity (roads are often seen as an impediment to habitat connectivity for other species), but apparently it wasn't always like that.

Stephen Mather, the first NPS director, noticed that most people were visiting the national parks by car in the early twentieth century and advocated for better road connectivity between the parks to increase their accessibility. Carr (1998) drives the point in Chapter 2 of his book Wilderness by Design: Landscape Architecture & the National Park Service that:

“The public was as vital to the success of national parks as was the scenery; without people there were no parks, only wild regions of the public domain, which, as such, were easily subject to other forms of ownership and exploitation.”

Hetchy Hetchy had been dammed for its water resources. The value of preservation versus conservation came to a head in the debate over whether Mount Rainier should be a national park or national forest. Hydroelectric power production, logging, irrigation, and grazing were some of the other activities historically proposed on national park lands. Scenic preservationists viewed tourism as a way to stave off these competing interests, and in the early twentieth century, cars were literally the vehicle to get people to parks.

|

| National Park-to-Park Highway map ca. 1927. Image credit: Department of the Interior and National Park Service; National Highways Association via Dr. Caroline M. McGill Personal Papers Collection at the Montana State University Renne Library. |

Like Frederick Law Olmsted's “Emerald Necklace” in Boston, but on a much larger scale, the National Park-to-Park Highway would provide road connectivity between twelve national parks across nearly as many states long before Eisenhower conceived of interstate highways in the 1950s. To publicize the project, various stakeholders embarked on a road trip in 1920 covering over 5000 miles in 76 days over tough roads. Less than a third of the roads were paved. Mather organized caravans in 1925 for publicity, and the national parks saw a record two million visitors that year.

Google Maps estimates the trip at about 4000 miles and 69 hours of driving time. Perhaps the Google route is slightly different (I did have to leave a couple points out because you're only allowed to input ten points) or some roads have been straightened or otherwise improved. If one were to actually drive this route, I imagine the detours one would be compelled to take would easily accumulate to bridge the difference. In any case, it certainly sounds doable in seven weeks, but on the other hand, I imagine you could spend seven weeks in any one of these parks and not want to leave.

I decided to take a virtual tour of the twelve parks and learn one thing about each one. Here's what I learned:

Rocky Mountain National Park

|

People have been using the park area since 10000 BC.

Photo credit: Max and Dee Bernt.

|

Yellowstone National Park

|

Wolves were exterminated from the park by 1926, but were reintroduced in 1995.

It's controversial. Photo credit: Esther Lee.

Glacier National Park

|

|

| Comparison of historical photographs to modern imagery shows the glaciers are retreating. According to a 2010 estimate, they may be gone by 2020. Photo credit: Giggs Huang. |

Mount Rainier National Park

|

| Ecological restoration at the park helps to stave off invasive species and mitigate the impacts of human use. Photo credit: Navin75. |

Crater Lake National Park

|

| Crater Lake is the deepest lake in the U.S. and ninth deepest in the world. Photo credit: Andy Melton. |

Lassen Volcanic National Park

|

| Lassen has four different types (PDF) of volcanoes. Photo credit: LassenNPS. |

Yosemite National Park

|

| Yosemite has over 60 properties listed on the National Register of Historic Places, including the Ahwahnee Hotel (the Ahwahneechee tribe used Yosemite long before westerners discovered it). Photo credit: Esther Lee. |

Kings Canyon National Park

|

| Efforts have been made to remove human activity from the Giant Forest. Photo credit: Tom Hilton. |

Sequoia National Park

|

| After suppressing fire for almost a century, turns out fire facilitates germination and recruitment, reduces competition, and reduces fire hazard (read more). Photo credit: Mark Doliner. |

Zion National Park

|

The patterns in the Navajo Sandstone are a result of changing wind patterns. Photo credit: Zion National Park.

|

Grand Canyon National Park

|

| Soil surveys exist for less than a fourth of the park. Photo credit: Grand Canyon National Park. |

Mesa Verde National Park

|

| Ancient Pueblo lived here for over 700 years. Mesa Verde contains 600 cliff dwellings and 5000 archaeological sites. Photo credit: Mike Steele. |

Have you been to any of these parks? What did you do there? Did you drive the Park-to-Park Highway loop? What were the highlights? Is there one park in particular that tops your bucket list?

_

Sources and more information:

http://www.pbs.org/nationalparks/history/ep4/2/

http://pavingtheway.tv/about_film.html

Montana State University Renne Library

Wikipedia

(Also, see links embedded in article.)

No comments:

Post a Comment