|

| Photo credit: Bob Wick (Bureau of Land Management via Flickr). |

We're still about ten days away from the official NPS centennial, and I'm continuing to learn more about our national parks. There are so many interesting places, just as much history, and not enough time.

In reading about NPS history, one of many events that stood out to me was a David and Goliath story about the Nez Perce (also known as the Niimiipoo, more on names later). In the next few paragraphs, I've written down everything I've learned about the Nez Perce National Historic Trail, which is just enough to know that I have barely scratched the surface of this subject and probably only got the general gist of things right. Near the end of the post, I've listed several resources with further information for anyone interested. Here goes.

|

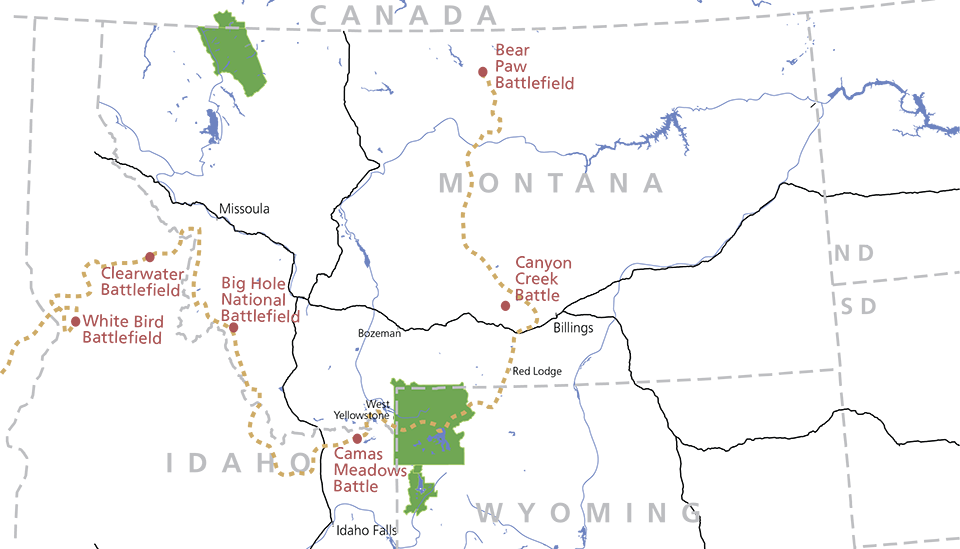

| The Nez Perce National Historic Trail was established in 1986 to mark the 1170 mile pursuit of over 750 Nez Perce by the US Army in 1877. Image credit: NPS / Yellowstone Spatial Analysis Center. |

Last week, on August 9, a century and thirty nine years ago, soldiers snuck up on unsuspecting and unarmed Niimiipuu (pronounced nee-mee-poo) - two thirds of which were women and children - in the early hours of the morning and killed them. Ninety Niimiipuu and about 30 army soldiers and volunteers were killed in what became known as the Battle of Big Hole.

The third of about 20 confrontations between the Niimiipuu and US Army, Big Hole appears to have been a significant turning point. The earlier battles had been clear victories for the Niimiipuu, and Chief Looking Glass had assumed the worst was over when his people set up camp at a familiar spot in Big Hole Valley to rest on August 7. Unfortunately, the soldiers spotted the camp the next day.

|

| The Big Hole National Battlefield in Montana is part of the NPS, but the Historic Trail is managed by the Forest Service. Photo credit: Sue Ruth. |

Despite the element of surprise, the Niimiipuu were quick to organize an effective defense. They cornered the soldiers under lodgepole pines for 24 hours, enabling their people to escape.

Big Hole was technically another victory for the Niimiipuu, but the battle seems to have created an irreconcilable rift. Up until Big Hole, the Niimiipuu endeavored to pass peacefully through the settlements along their route, but the battle seems to have destroyed any hope for peace.

|

| Big Hole battlefield viewed from higher ground. Photo credit: Sue Ruth. |

For thousands of generations before western settlers arrived, as much as 10000 years ago, long before horses were introduced in the 1700s, Niimiipuu ("The People") walked great distances in the Northwest to visit friends and relatives and other tribes, trade for goods, and hunt buffalo. An old legend says grizzly bears befriended a young boy in the region, showed him a path through the treacherous mountains, and taught him how to survive out there. The Niimiipuu trekked back and forth from their homeland between the Cascades and Rocky Mountains to the Oregon coast, and aided Lewis and Clark along a particularly difficult section of the trail called Lolo Trail or Lolo Pass in 1806. Lewis and Clark actually had to turn around for the first time ever at the Lolo Trail, and returned for a second successful attempt with Niimiipuu guides to help them.

|

| Photo credit: Forest Service Northern Region. |

To make room for settlers, the US government incrementally took much of the Niimiipuu ancestral lands away. In 1860, people found gold on the Niimiipuu reservation, leading to the government reducing Niimiipuu land to one-tenth of what it had been after the previous reduction eight years earlier.

Some of those displaced refused to agree to this and did not want to leave their homeland. In 1877, the government ordered those displaced to relocate to a reservation elsewhere in Idaho. They did not want to leave, but as they were preparing to, some of the younger Niimiipuu exacted a revenge on settlers for the killing of their families, and the tension just seems to have escalated, leading to the army chasing the Niimiipuu, and the Niimiipuu fleeing.

|

| View from along the trail. Photo credit: Forest Service Northern Region. |

But as I understand it, the Niimiipuu weren't fleeing for their lives. They were on the move because they didn't want to be captured and relocated. They were on the move because they wanted to avoid conflict. They sought out friendly tribes further east to join, originally planning to join the Crow tribe, but that didn't work out, so they planned to meet Sitting Bull in Canada.

After a nearly 1200 mile journey, the soldiers caught up with them at Bear Paw, just 40 miles from the Canadian border. Of the 800 that started the trek in Oregon, 200 escaped across the border and about half surrendered (another source says half were killed in the battle). The NPS says (see links to brochures further below) it was the combination of the Big Hole loss and the loss of many Niimiipuu chiefs and warriors that led to the surrender.

The Niimiipuu surrendered because they were told they would be taken back to their homelands, but were actually taken far away to Fort Leavenworth, Kansas, and then to Oklahoma.

About 500 Niimiipuu in total were captured, but only 301 survived the difficult living conditions in these faraway places. Some were eventually allowed to return to Idaho, but others, including Chief Joseph, were not. Instead, they were relocated nearly a decade later to the Colville reservation in Washington state.

|

| Six scenes from the Nez Perce war and surrender of Chief Joseph. Published in Harper's Weekly in 1877. Image credit: Library of Congress (click link to view larger on LOC website). |

Apparently various tribes in the area did not necessarily support the Niimiipuu cause or sympathize with their situation: they did not condone the violence the Niimiipuu unfortunately became embroiled in. At times it sounds like members of other tribes were actually working against the Niimiipuu.

While all of this was happening, there was also a shift in religious beliefs underway amongst the Niimiipuu. Some chose to retain traditional beliefs while others converted to Christianity. Did those converted to Christianity return to Idaho while those that followed the Niimiipuu ways end up in Washington? It sounds like that happened in at least a couple of cases, but whether that was the exception or the rule or just a coincidence requires more research.

Women and children comprised most of the displaced.

|

| Photo credit: Edward S. Curtis (1868-1952) via Library of Congress. |

Delve deeper into the subject:

- A good place to start is with Chief Joseph's story, written by Martha Perry Lowe and copyright 1881, available for free online. This is a very quick but powerful read.

- A good place to visit next is this short video.

- Here's another video with a slightly different story that points out the irony in the Nez Perce aiding Lewis and Clark, whose exploration work facilitated the expansion that led to this unfortunate series of events.

- If you're curious about what the trail looks like, consider watching Bart Smith walk the first portion of the trail in 2011 in his series of 25 short videos. Each video is probably about seven minutes long. If you don't have that much time, I recommend starting with the twelfth video. The route looks designed for driving, but Smith says "it just...shows how badly the Nez Perce wanted to keep their ancestral life and their original homeland...actually walking it, I really get a strong sense of the [non-treaty Nez Perce's] determination." I believe this is the book (newer edition) Smith was reading as he walked.

- The NPS has two succinct brochures about the trail, also available in German and Japanese languages.

- Yellow Wolf was a Niimiipuu warrior that worked with a biographer to document his story. You can read or download the whole book for free here.

- The Niimiipuu created a special breed of horse well-suited to the area's environment by crossing Appaloosa with Akhal-Teke. Watch a video about them here.

- Hear what the Nez Perce language sounds like in this video.

- This book has the most reviews of all the books I've seen about the Nez Perce on Amazon, and has nearly 5 stars.

- Link to Nez Perce Trail Foundation: http://nezpercetrail.net/

- Forest service trail page: http://www.fs.usda.gov/main/npnht/home

What's the difference between "Niimiipuu" and "Nez Perce"? I've used both in this post, and you may be wondering what they mean and where they come from. I sure did when I first ran into these terms. As I understand it, Niimiipuu is the proper name of the tribe, and "Nez Perce" was a name somebody from the Lewis & Clark expedition gave the Niimiipuu that stuck. I think Smith says in one of his videos that the guy mistakenly thought he saw a Niimiipuu with piercings and so used the name Nez Perce, which translates in French to "pierced nose". Wikipedia says something similar, and identifies the guy as an interpreter on the expedition, but doesn't cite a source. If you check out that Wikipedia page, don't miss the many interesting images there (like the one below).

|

| Nez Perce camp at Lapwai, Idaho in 1899. Photo credit: Wikipedia. |

Here's what I really want to know: is there a trail you can't wait to walk? Would you be willing to do 1200 miles on foot anywhere?

_

Sources and more information:

http://www.fs.usda.gov/detail/npnht/home/?cid=STELPRDB5362845

https://www.nps.gov/yell/learn/historyculture/flightnezperce.htm

https://www.nps.gov/museum/exhibits/nepe/index.html

Landscape of History video on YouTube

NPS' two succinct brochures

Bart Smith's 25 video shorts on YouTube

(Also see the links embedded in this post.)

No comments:

Post a Comment